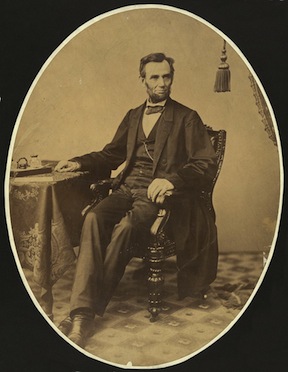

Any mention of, much less any anniversary associated with, Abraham Lincoln evokes a lump in the throat and palpitations in the heart of even the most casual reader of history. April, 2015, saw the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. There are so many great Lincoln biographies and essay collections out there. Among my favorites is David Herbert Donald’s Pulitzer Prize winner Lincoln.

It is no wonder Abraham Lincoln evokes our deepest feelings and thoughts. There are few figures throughout history who dominate a critical nexus of cataclysmic change, yet can also be labeled a “great soul.” Abraham Lincoln is one of these rare leaders.

You know the politics. The Union victory in the Civil War transformed the public’s perception of our country from a federation of states to the “one nation” it is today. On top of that, Lincoln shepherded the fractious country and government to free America’s slaves. Considering that slavery was the main source of wealth held by Southern aristocracy, that’s something.

Yet some important misconceptions about Lincoln haven’t entirely worked their way out of the public’s consciousness. For example, most of the major historians after the war were Southerners. These writers tried to label the conflict “the War Between the States,” inferring that the United States was a confederation of states, with perhaps the legal right for states to secede. Today, the appropriate term, “Civil War,” is nearly universal, with “War Between the States” buried in the dustbin of history.

One misconception about Lincoln that still persists is that he felt ambiguous about slavery. Nothing could be further from the truth. Just read his Coopers Union speech, which propelled him from a relatively obscure politician to national prominence as the front runner for the Republic presidential nomination. There is no ambiguity in that abolitionist-like speech. That, as a politician, he tried to find a way to end slavery without war explains the compromises and ideas he advocated along the way. He believed slavery would die a natural death if it wasn’t allowed to expand. Also, he proposed a nation overseas to resettle slaves, which became Liberia. But, of course, with the value of bondsmen, the largest asset “owned” by the wealthy, powerful ruling Southern aristocracy, taking slavery away inevitably was going to require a trial by fire: war. Another myth created by early Southern historians was that the war wasn’t fought over slavery. Nonsense. Read this excellent book on this subject: The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery by Eric Foner.

A Central Theme of The Lies that Bind

Refuting the implicit and explicit lies about slavery is central to my forthcoming novel, The Lies that Bind (to be published by TouchPoint Press, 2015). One of the protagonists, the visionary charlatan Durksen (Durk) Hurst, aka “Dark Horse,” forms a secret partnership with a group of slaves to build their own egalitarian plantation. This deception is the Dark Horse partners’ subterfuge to work their way around the controlling hypocrisy of a slave/caste society in which they are stuck. These and my other characters must contravene many lies—including gender, race, and slavery—that can only take them so far, until history’s transcendent tides make them face the truth. Indeed, even my fictitious Southern hamlet’s richest aristocrats, the powerful French family, are bound by lies even more than the average citizen. Doesn’t this dramatization in history parallel the ambiguous nature of our own lives and society today?

In Lies, using drama, I try to dispel some of the myths associated with slave society. In his second inaugural address (http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/inaug2.htm), President Lincoln speaks of war as being the logical consequence of Southern wealth compiled by the sweat and blood of slave labor. In my novel’s secret partnership, where black and white men are virtually equal, their successes are the result of all the partners’ labors and talents. In fact, much of the brainwork behind the plantation’s success is from the wise and experienced Big Josh, a slave. In reality, have we always recognized the contribution slaves made to helping build America?

Fortunately, we no longer believe the myth of the “happy slave.” Studies show a startlingly high percentage of slaves died from overwork, inadequate nutrition (slaves were always hungry), and maltreatment. As a result, not surprisingly, emotional depression in slave quarters was universal. Would you have been happy? To maximize their investment yield, slave owners worked their human chattels long hours, kept feeding costs to the barest minimum, and used harsh methods, especially the lash. A good study of slavery (interestingly, with parallel illustrative sections on white men enslaved in Africa) is John W. Blassingame’s The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South.

In Lies, the Cassandra-like fugitive Antoinette DuVallier predicts that war is inevitable, saying of the Southern aristocracy, “The fools are hell-bent to ride on white horses under brave banners, sabers waving and plumes flying, and bring this land to waste and ruin. To drown their fortunes, families, and lives in rivers of blood—and nothing will stop them.” In truth, the South seceded when Lincoln was elected because it knew he wanted to end slavery. Period. Any other explanation is false, an attempt to build and maintain a myth.

There is one anomalous section toward the end of Lies that refers to the bravery of both the Confederate soldiers (most of whom did not own slaves) and the Union soldiers. This narrative hopes to dramatize what Lincoln went through in guiding the war effort to its conclusion. It also dramatizes his heavy-hearted burden for the suffering the war inflicted on both sides, upon the families, the widows and orphans, he addressed in his second inaugural.

And this is where Lincoln’s assassination most harmed the country. Lincoln told Grant, “Let (the South) up easy.” His policy for the future was, as he most eloquently stated: “With malice toward none, with charity for all.” Had reconstruction been effected under Abraham Lincoln’s benevolent hand, the devastated South might have recovered a hundred years earlier than it actually did. And this is the greatest tragedy about Lincoln’s assassination; that after he was shot, he then belonged “to the ages” rather than to the nation that so badly needed his great wisdom and charitable spirit.

Next Week: Meet Devereau French’s mother—and master manipulator—the reclusive Missus Marie Brussard French, who Turkle’s residents believe “sits in her dark room playing chess against God.”

Watch for publication of Ed’s novel, The Lies That Bind (TouchPoint Press, 2015), a darkly ironic antebellum mystery/drama set in Turkle, Mississippi, 1859-61. Ed Protzel’s views, opinions, and ideas expressed in this blog are his alone. Blog copyrighted by Ed Protzel © 2015.

To reach Ed’s publisher regarding The Lies That Bind:

Contact TouchPoint Press www.touchpointpress.com